|

|

A Room for London: Olympic Year 2012

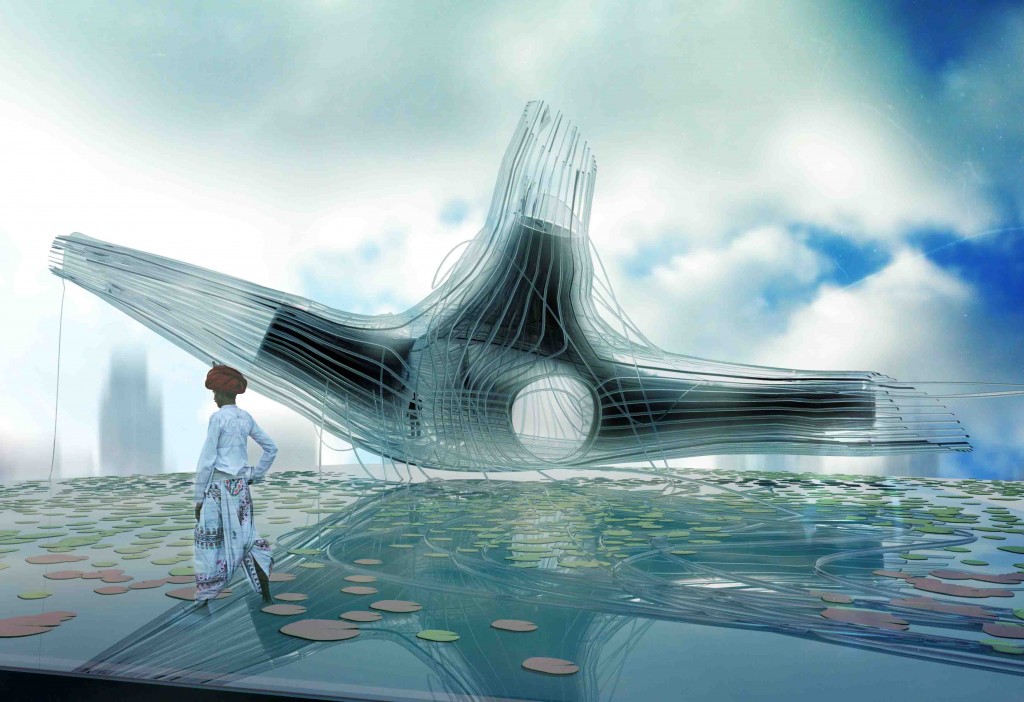

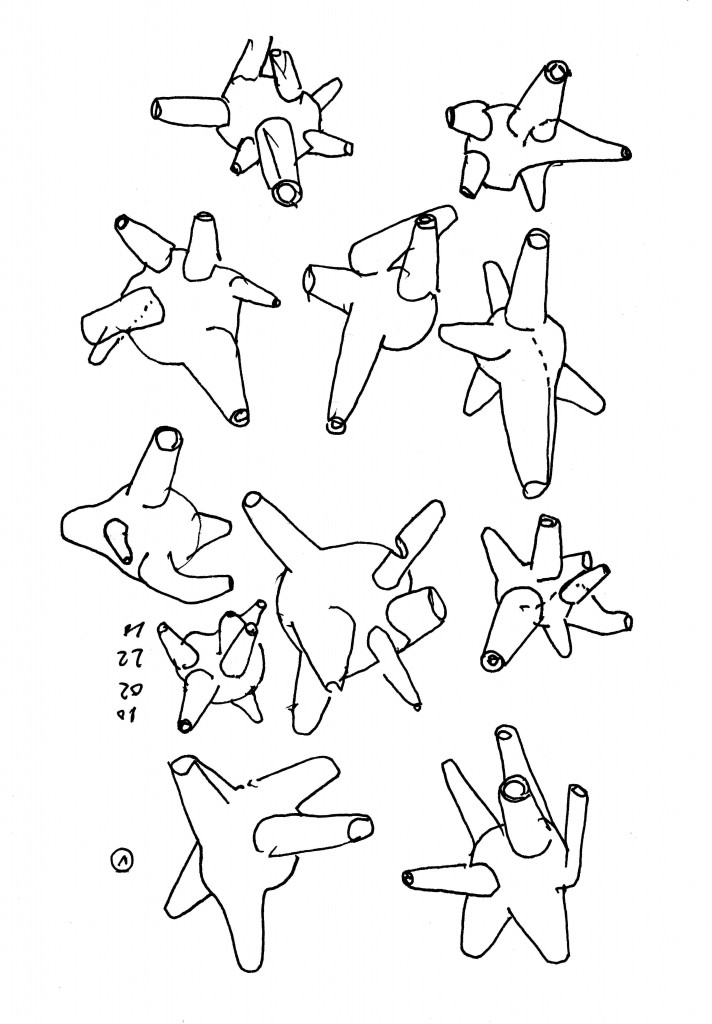

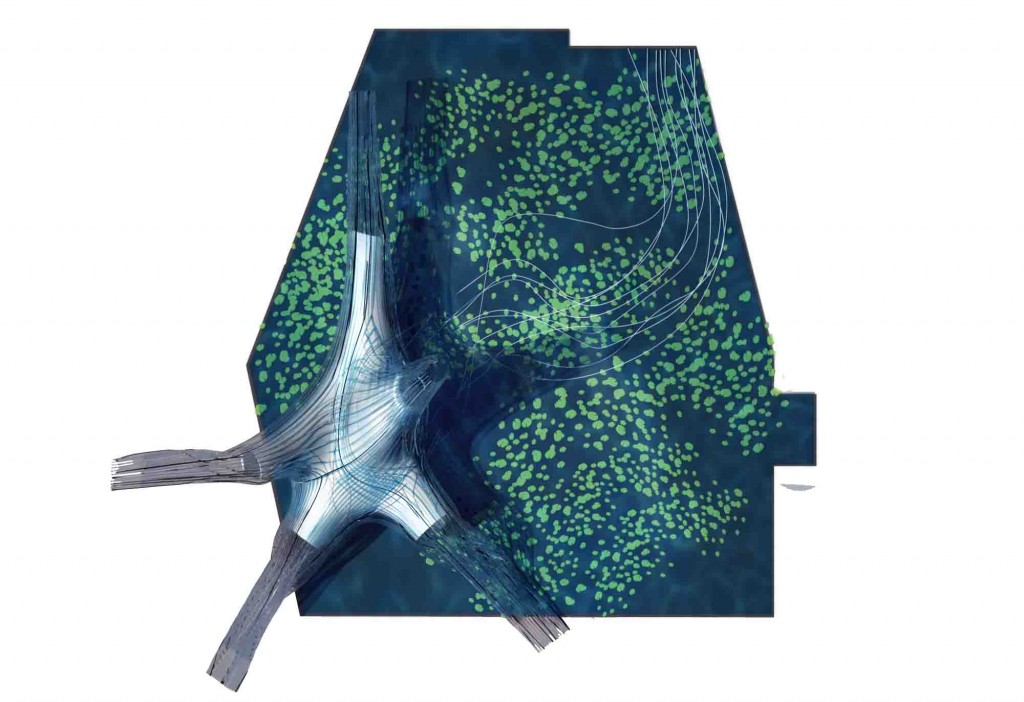

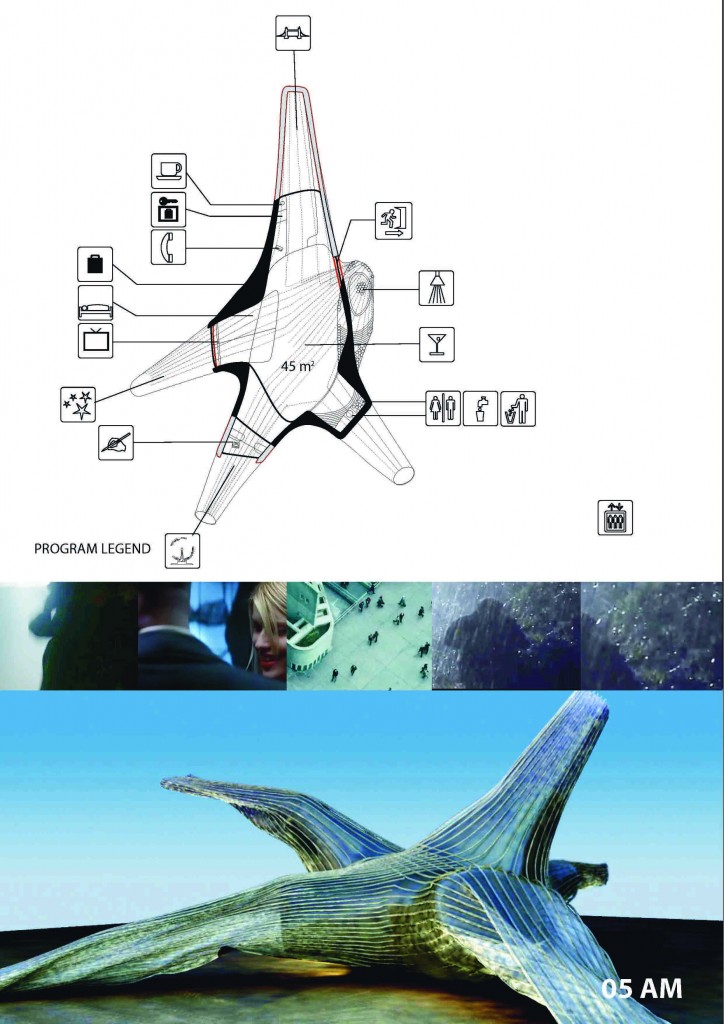

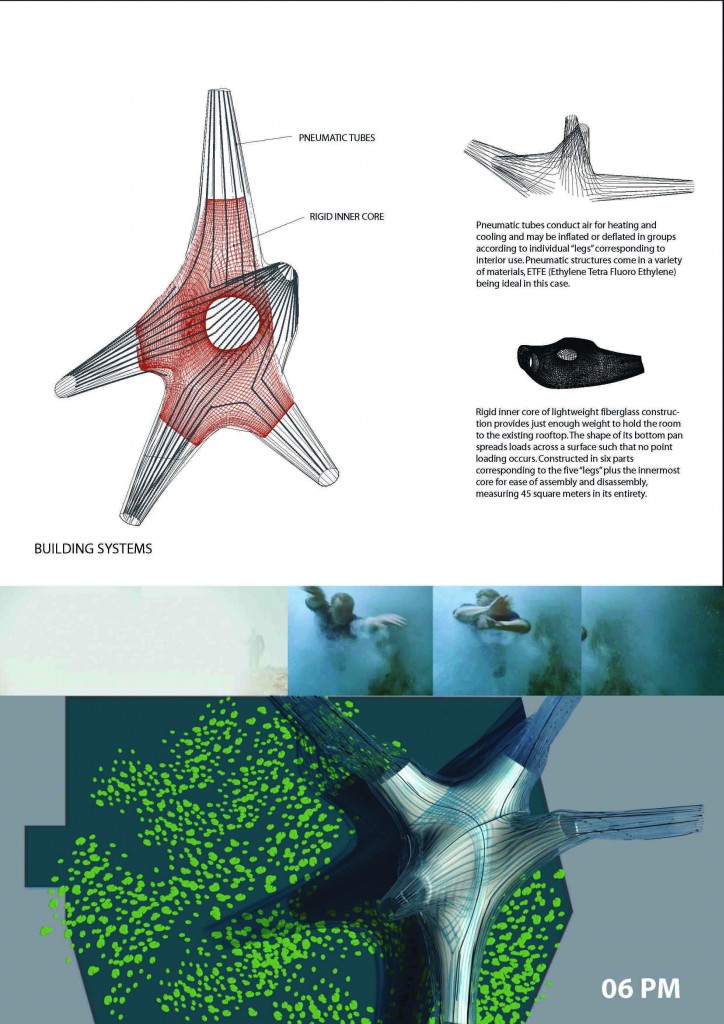

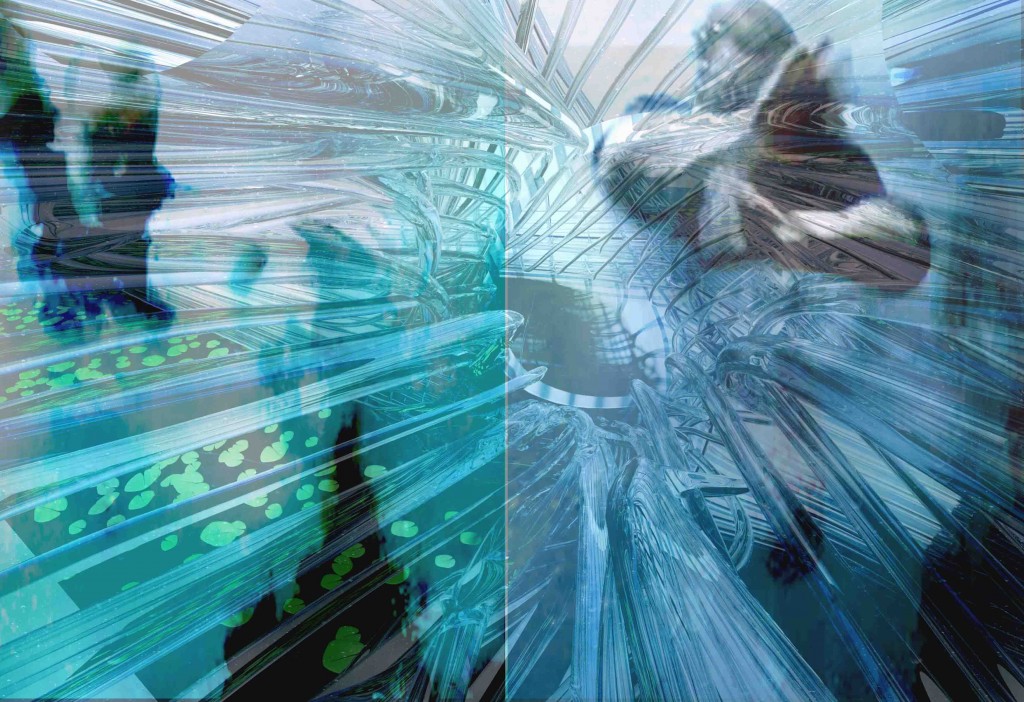

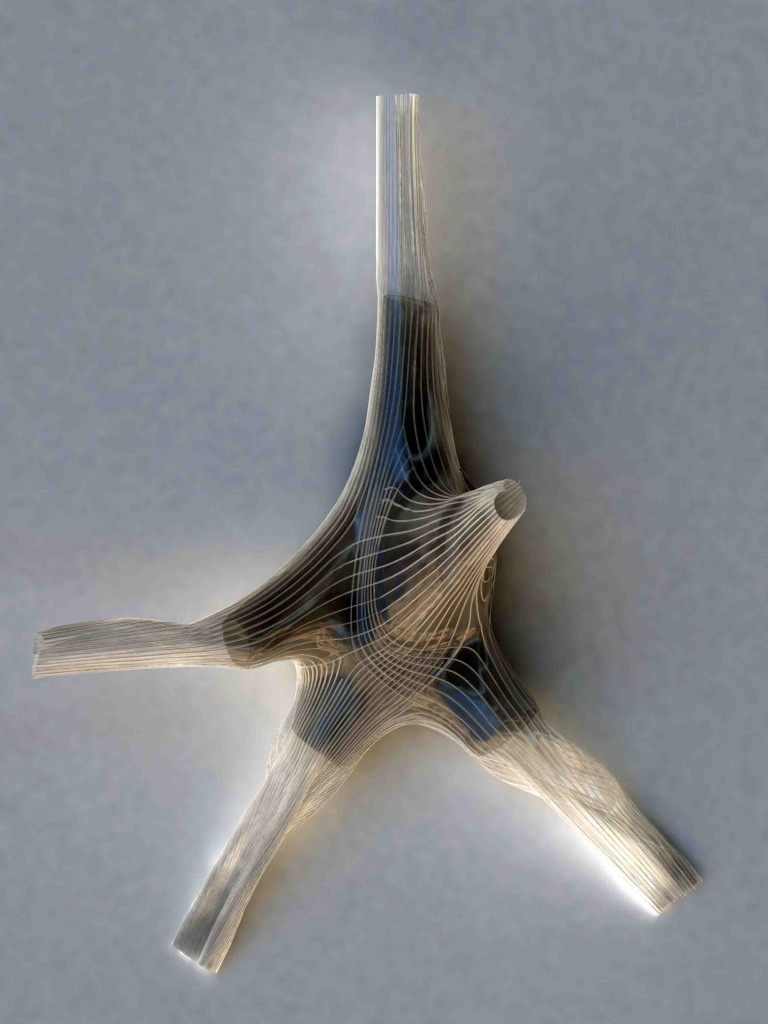

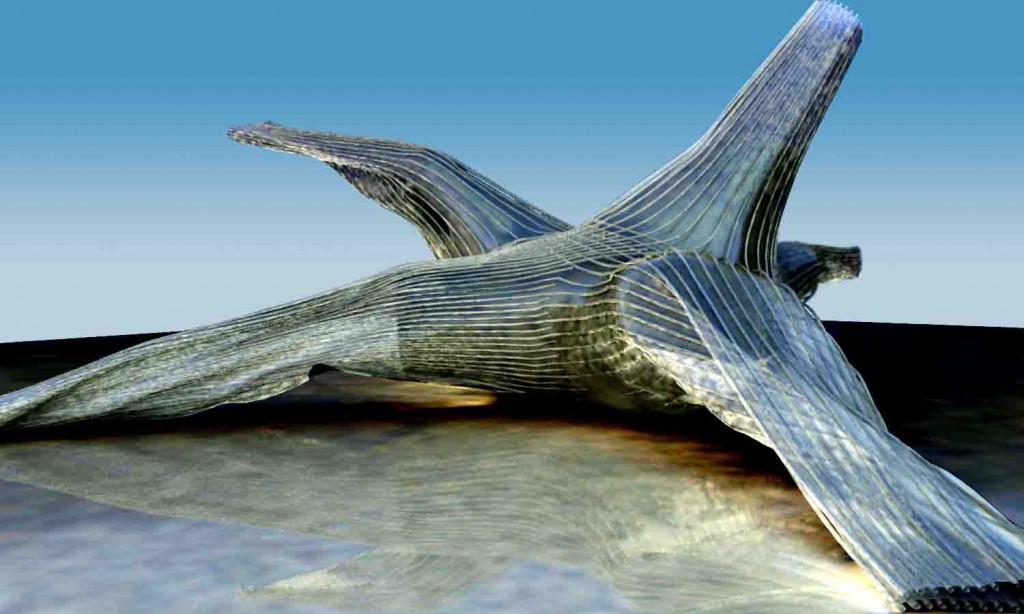

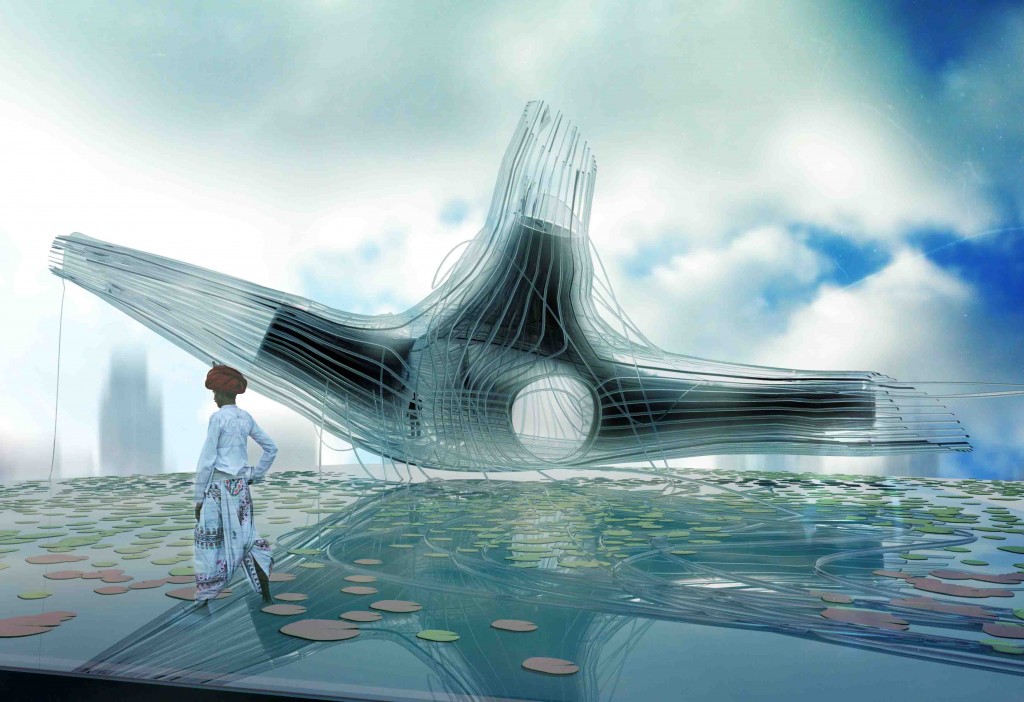

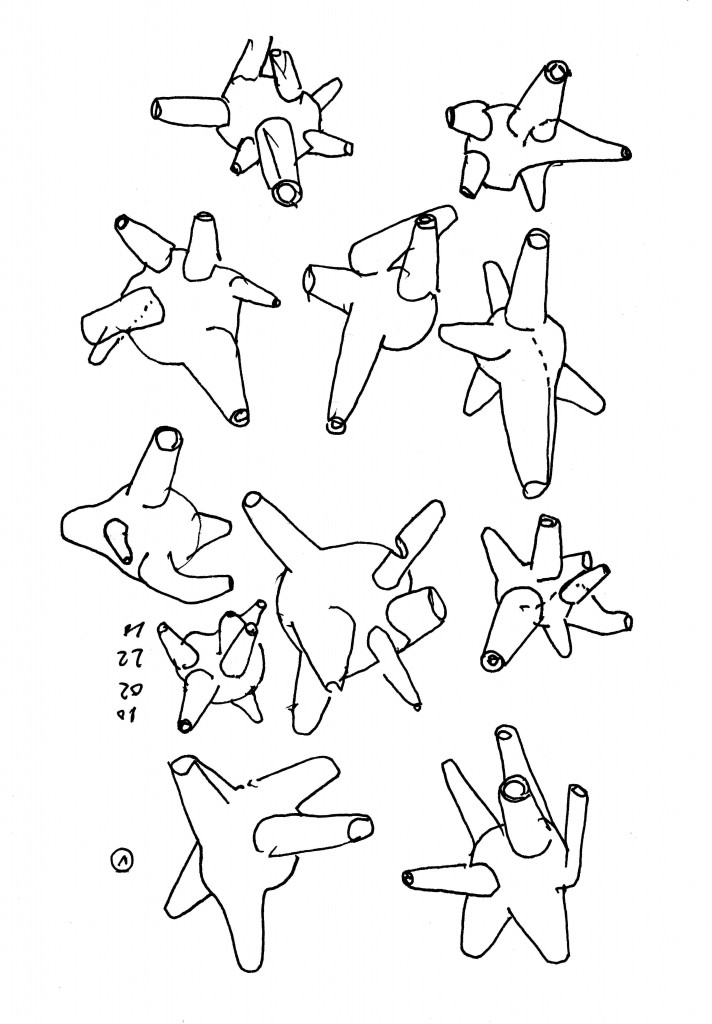

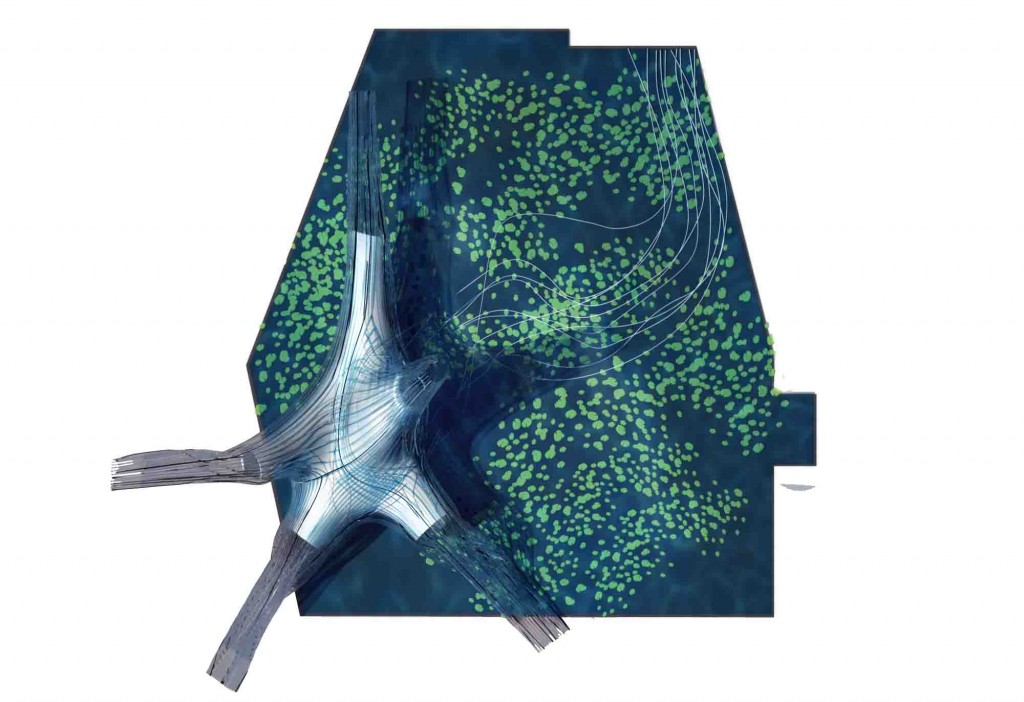

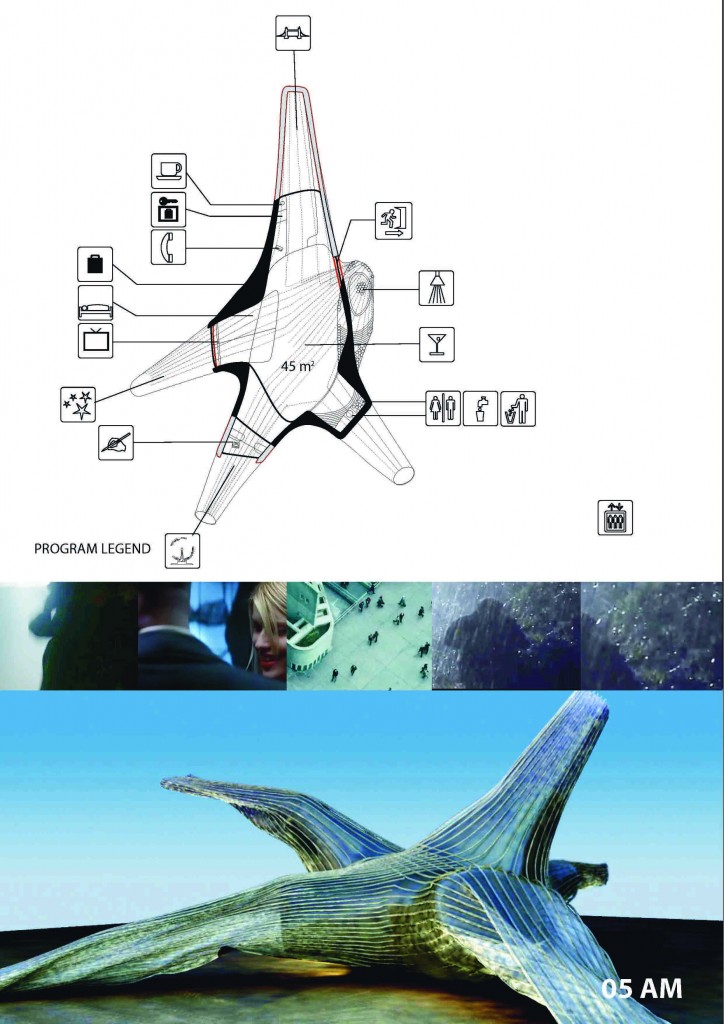

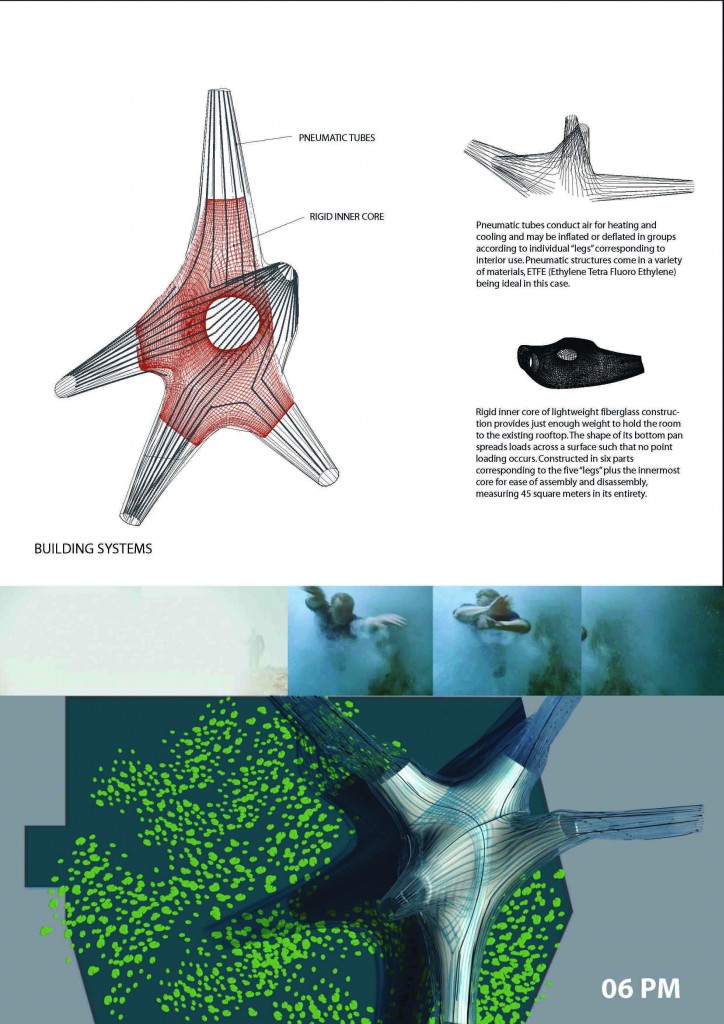

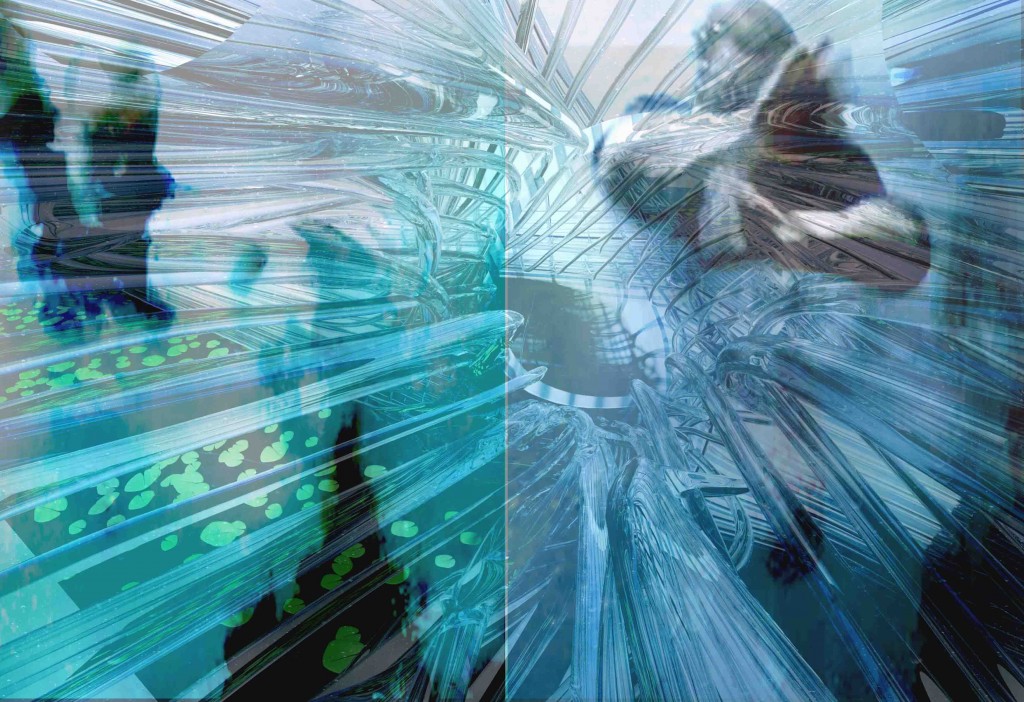

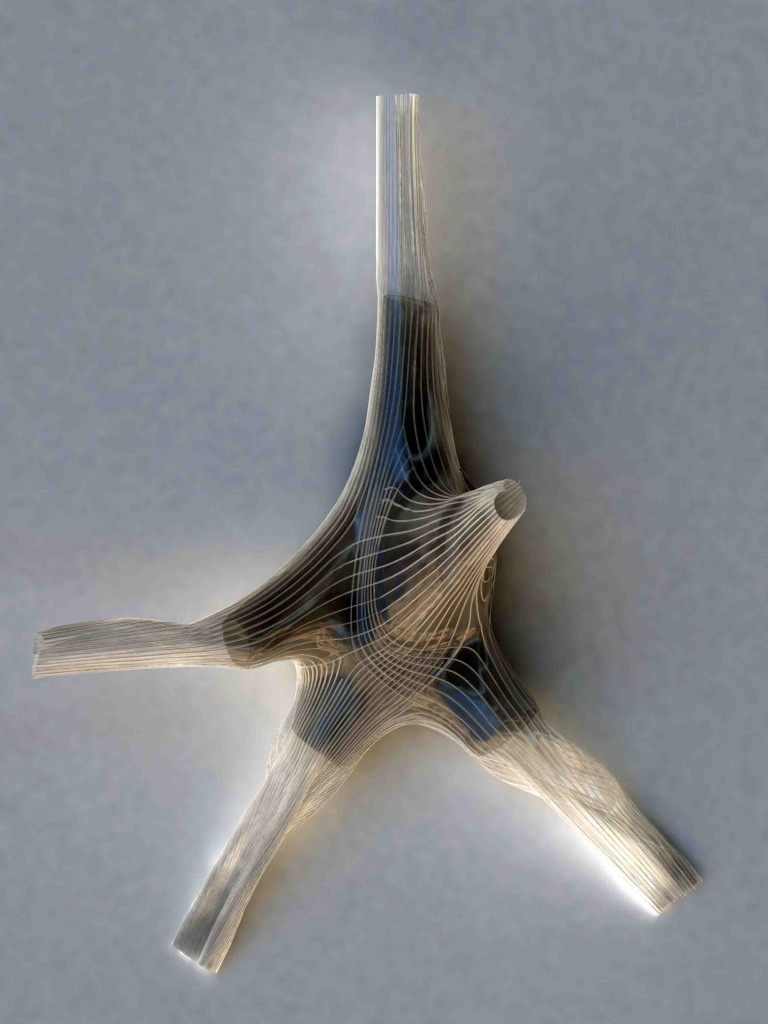

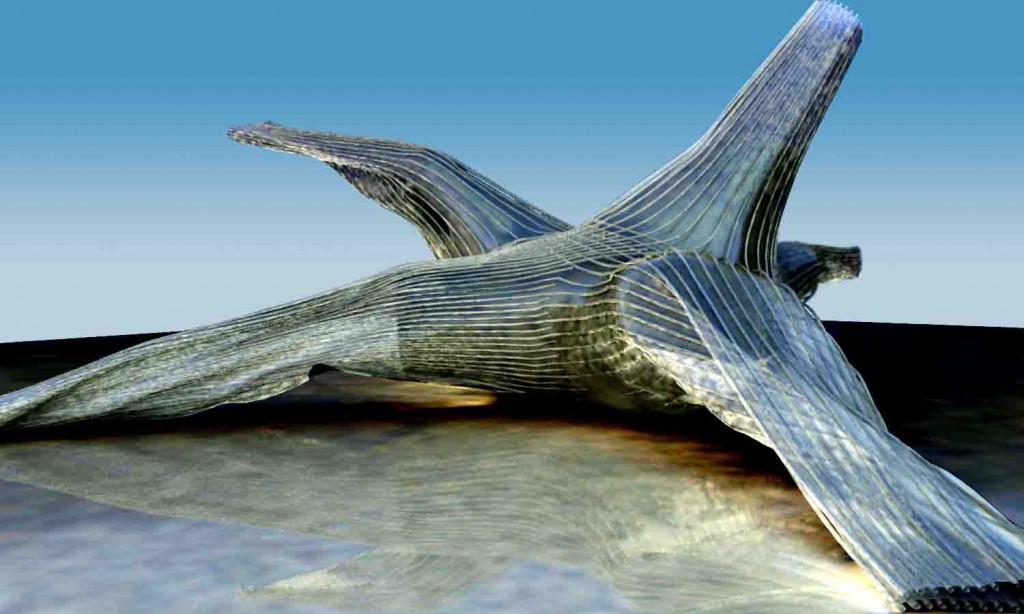

It is said that the weather in London leaves something to be desired, but this seems unimaginative. Upon close inspection all manner of nuanced weathers pass over the rooftops of the city, especially during the cooler months, laying down their delicate sheens of waterborne effects. Their capture is not technically difficult, requiring little more than differentiated surfaces that attract condensation. This twist on London’s weather and its effects promote re-orientation of an occupant’s sense of the city’s visual delights in an absolutely contemporary and opportunistic mode, one that integrates our interests in the fusion of architecture, art, engineering and climatalogical concerns. Up close and personal, London’s fogs, rains, sleets, and mists produce the natural material cloak for this room and rooftop. Sunny days and moonlit nights work as well, as light passes through the transparent body to the spaces within while simultaneously reflecting outward to the city beyond. In this way, tired notions of “high season” and even “four seasons” are rendered meaningless. In our proposal for A Room For London, its surfaces and ambiance multiply such crude distinctions into dozens of microclimatic conditions, effects, and sensations. A convergence of weather, ambiance, and occupancy, this proposal inverts the typical relationship between room and city, wrapping its guests in air-filled pillows of optical wonder. Outward appearances suggest a more complex form for this room than is actually the case: a five-legged starfish of sorts, pneumatically structured, set upon a blanketed membrane of impervious plastic atop Queen Elizabeth Hall. The rooftop blanket, wrinkled in places, catches moisture in its various guises and holds it for a time, long enough for proper aesthetic contemplation, before allowing it to drain properly through existing runoff channels and infrastructure. The room itself is comprised of a rigid translucent inner shell wrapped in a pneumatic double-skinned envelope of clear plastic tubes. Each of the five “legs” corresponds to a single function – bathing, sleeping, writing, etc. – and may be filled or deflated independent of the others despite the continuity of interior space across all of them. Thus, the daily vicissitudes of internal occupation are indexed by a changing external shape as legs inflate or sag according to use. For the guest, otherwise prosaic moments of everyday life are reframed through their juxtaposition with the novel behaviors of the dynamic skin. Over its yearlong lifespan the room becomes a character in the city, its moods vaguely associated with its different postures and moves, sometimes up, sometimes down.

In a sense, this room is turned inside out: radically exposed to a city and climate drawn close upon transparent walls, yet still providing the warm comfort of an environmentally controlled interior space. The clear envelope harvests whatever solar energy it can on clear days, then adds or subtracts as required through regulation of the air temperature within the pneumatic tubes. Additionally, the deflation of unused portions of the space minimizes energy use to only that which is necessary and allows the occupant to refine his or her carbon footprint according to individual desire and ethical sensibility. In this way, the room is not just literally transparent but environmentally as well, inasmuch as the degree of inflation or deflation serves as a visual registration of energy use. As required by the project brief, all services (water, power, and waste drainage) are drawn from the adjacent plant room of Queen Elizabeth Hall through conduit tubes similar in character to those of the pneumatic tubes. The structural ingenuity of pneumatic structures is well documented and seems an ideal solution for a project requiring minimal weight. Assembly and disassembly is achieved quickly as well, as each leg is constructed as a separate unit. Upon initial inflation, each is attached to the other to form the room, the assembly then tied to a single baseplate that spreads loads across its surface. Very few structural approaches are as fast, light, and inexpensive as this, and we dare say none are so full of delight. Beyond pragmatics, though, and however perverse it may at first sound, lies a contextual argument: pneumatic structures have long been part of the collective imagination of Londoners, from the utopian expressions of the 1960’s through contemporary expressions. A Room For London continues this lineage with a swerve through less obvious territory. Why, we ask, should the state of full inflation be the only pneumatic condition to which we aspire? After all, it really is just one possibility among so many others and is often the least subtle of them all. Our notion imagines the potential of deflation as much as it does inflation with an emphasis on the movement between each. What results has little to do with pneumatic experiments of the past that sought radical separation between inside and out; instead, we promote a more relaxed state of affairs in which distinctions between a room and its city are more complex.

Project Credits:

Russell Thomsen, Eric Kahn, Matt Au, Francisco Alarcon-Ruiz, in collaboration with Jason Payne/Hirsuta

About Russell Thomsen

A founding partner in the award winning Central Office of Architecture (COA, 1987-2008) and IDEA Office (2009-2014), Russell Thomsen formed RNThomsen Architecture in 2015. He has been a licensed architect since 1989. The office provides a full range of architectural services. In addition to directing the practice, Russell is also a senior design studio faculty member at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) in downtown Los Angeles. The work of the office has been internationally recognized, exhibited and published. The office has received several awards including the Architectural League Prize and Emerging Voices, both from the Architectural League of New York, and the Best In American Architecture Award for the Saitama Residence.

|