Thinking the Future of Auschwitz

|

Thinking the Future of Auschwitz

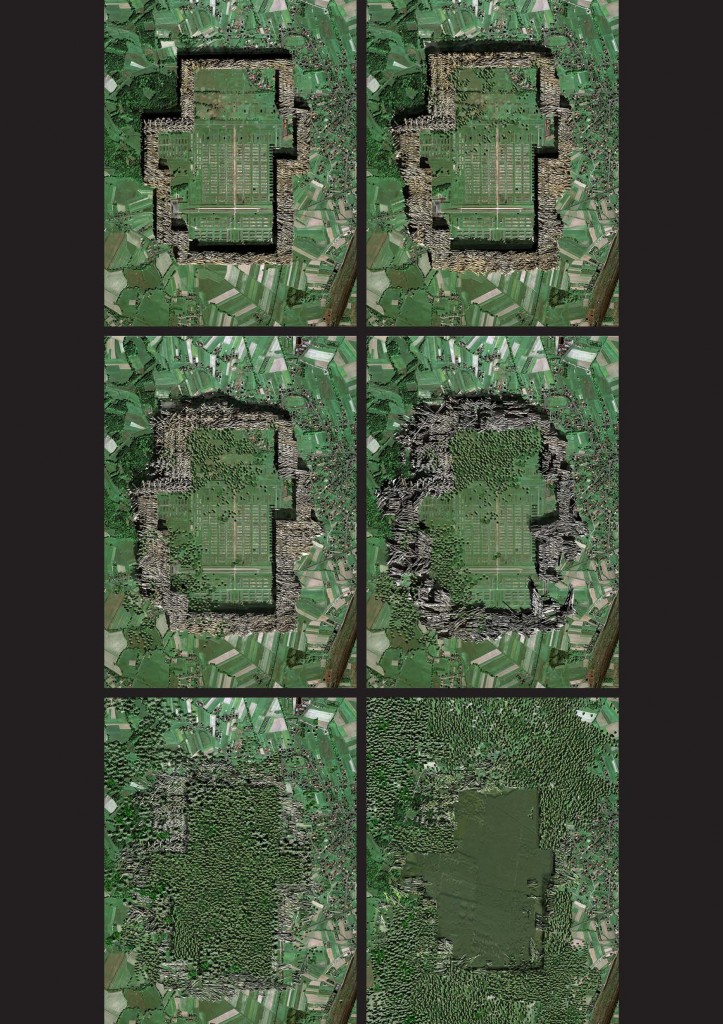

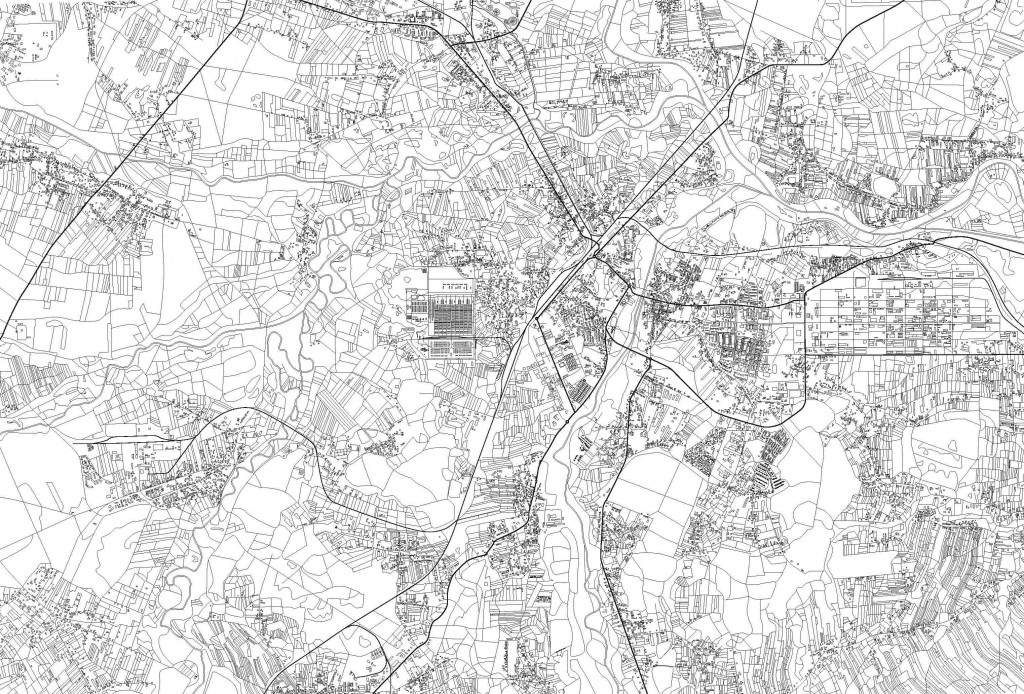

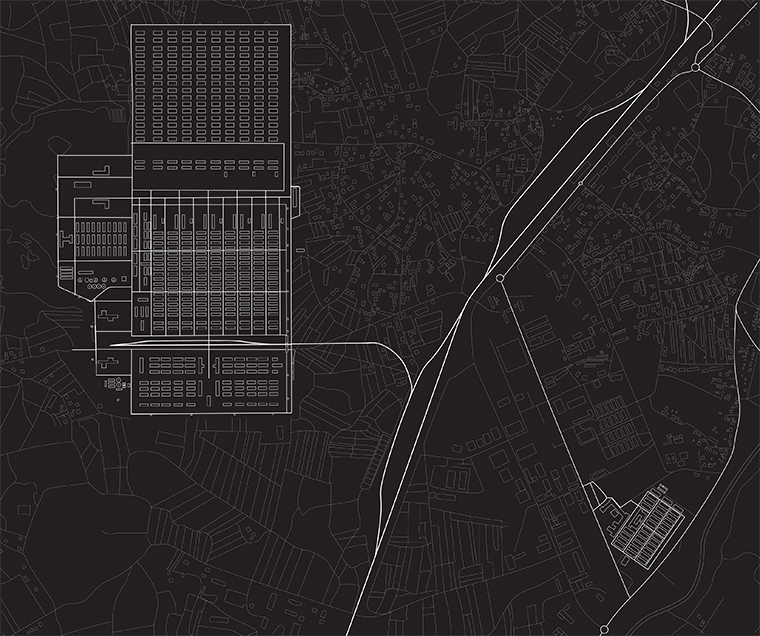

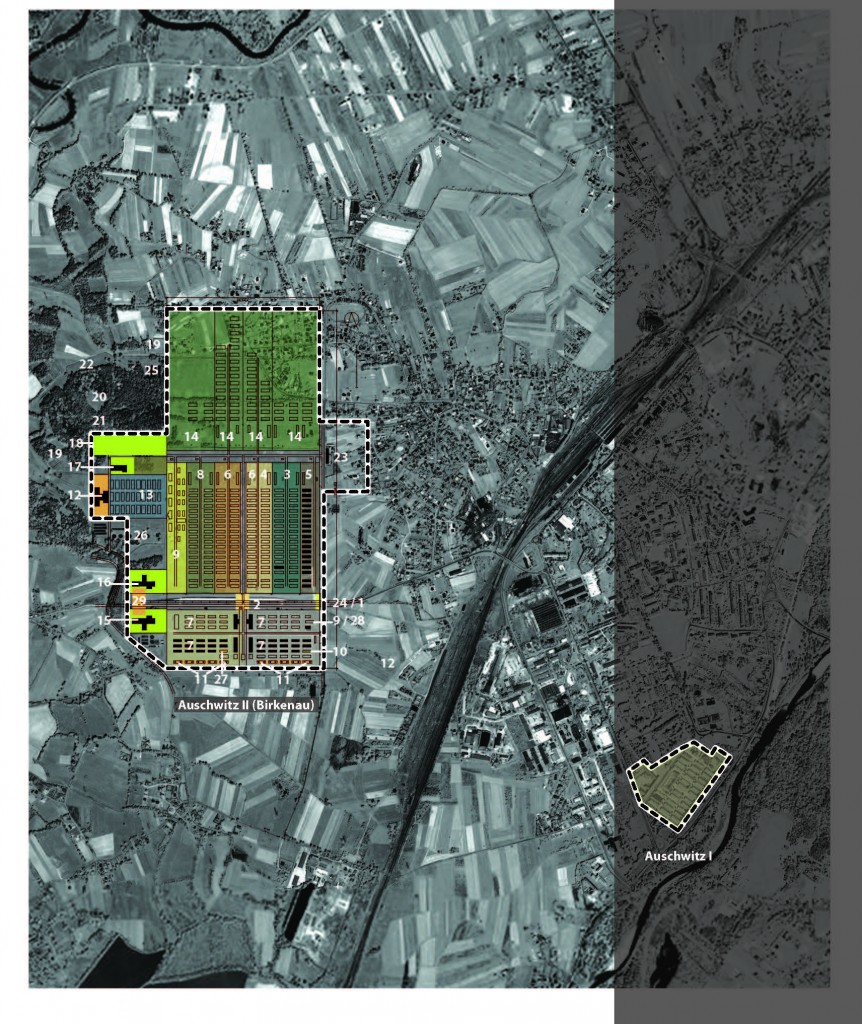

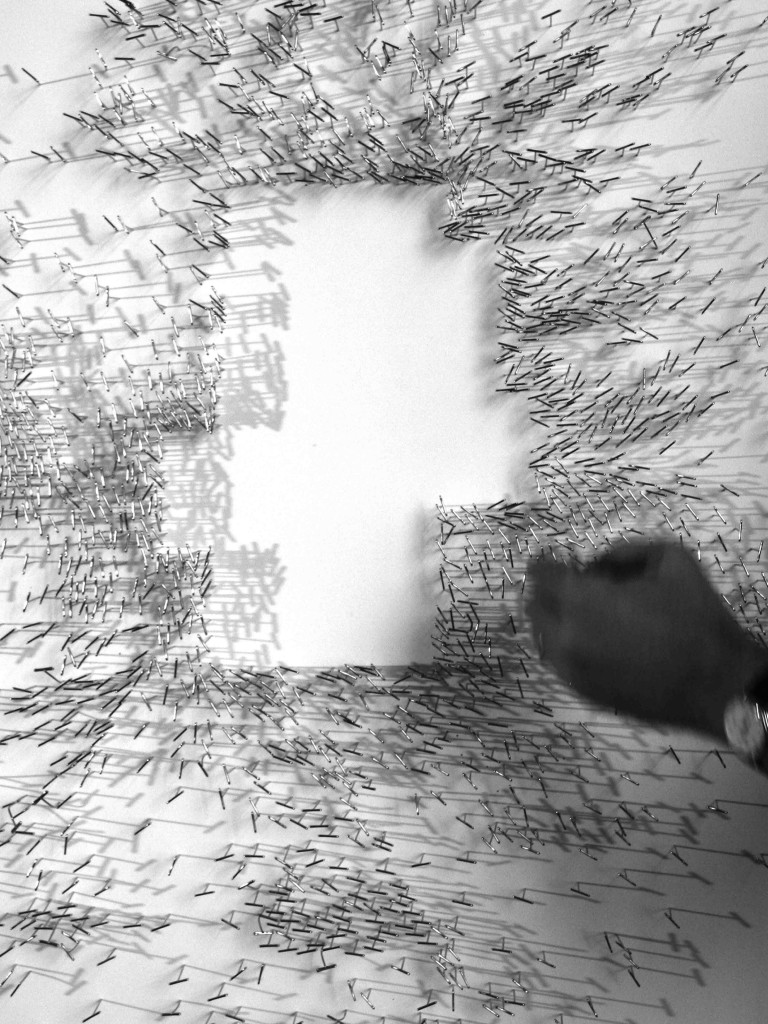

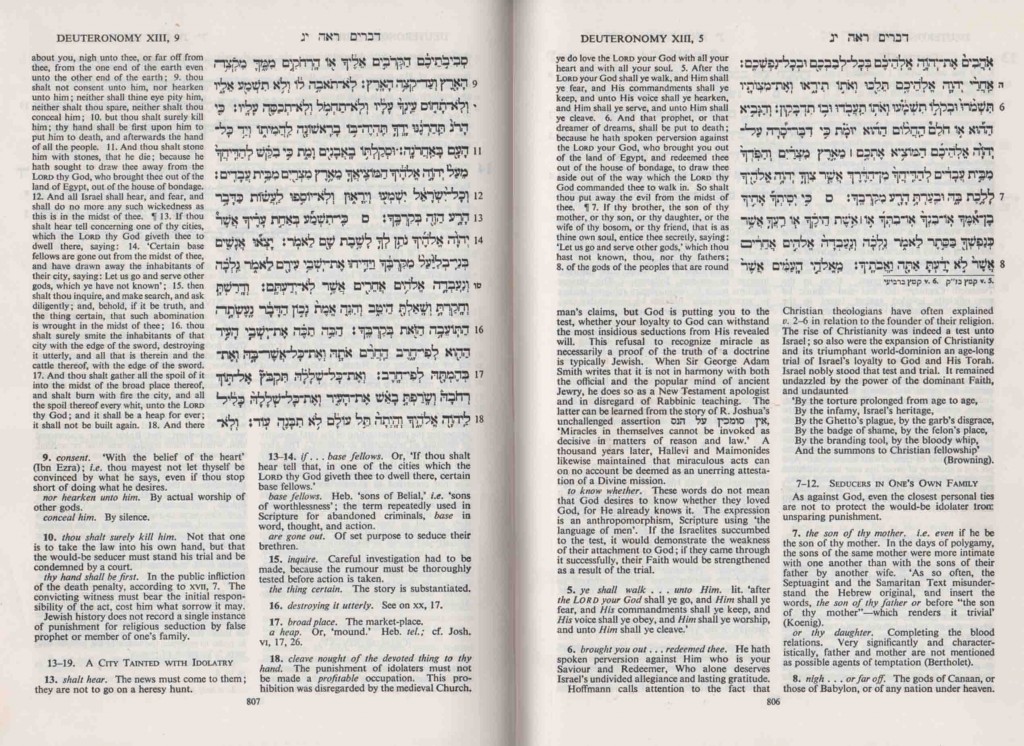

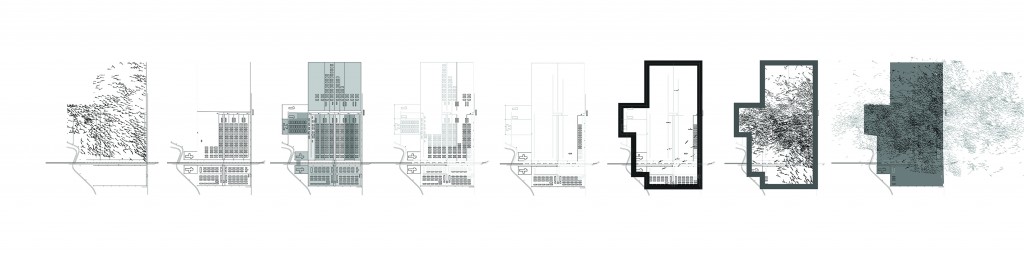

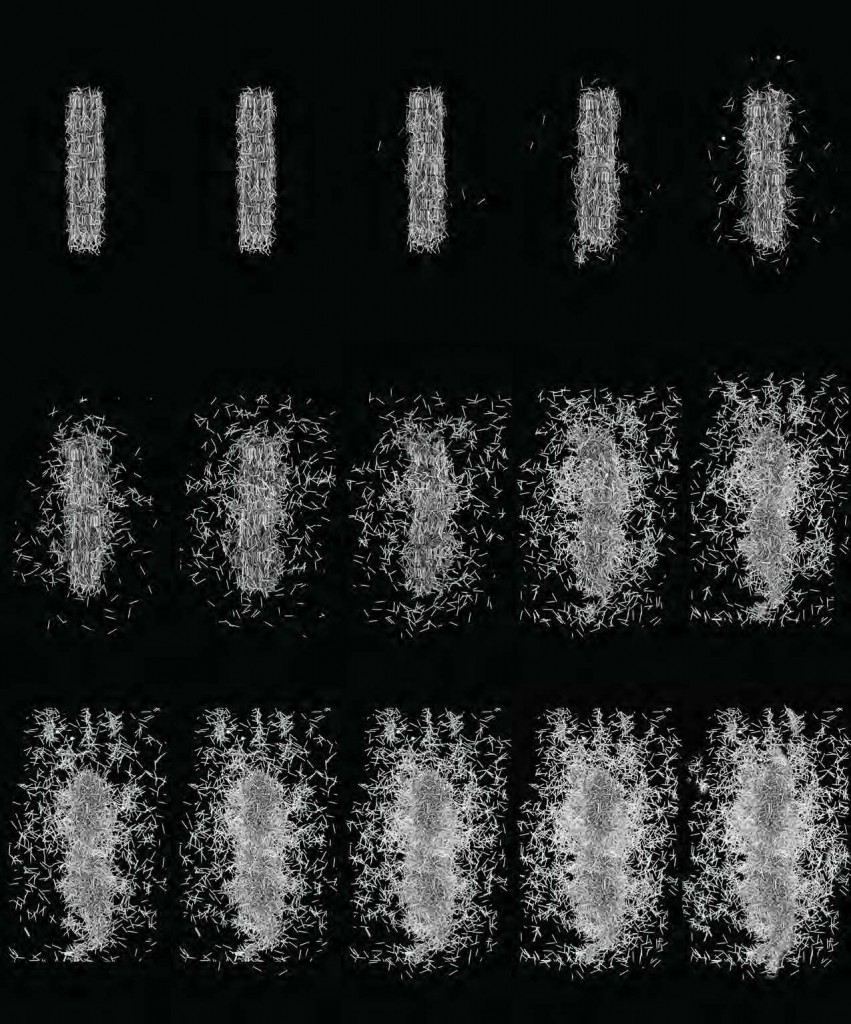

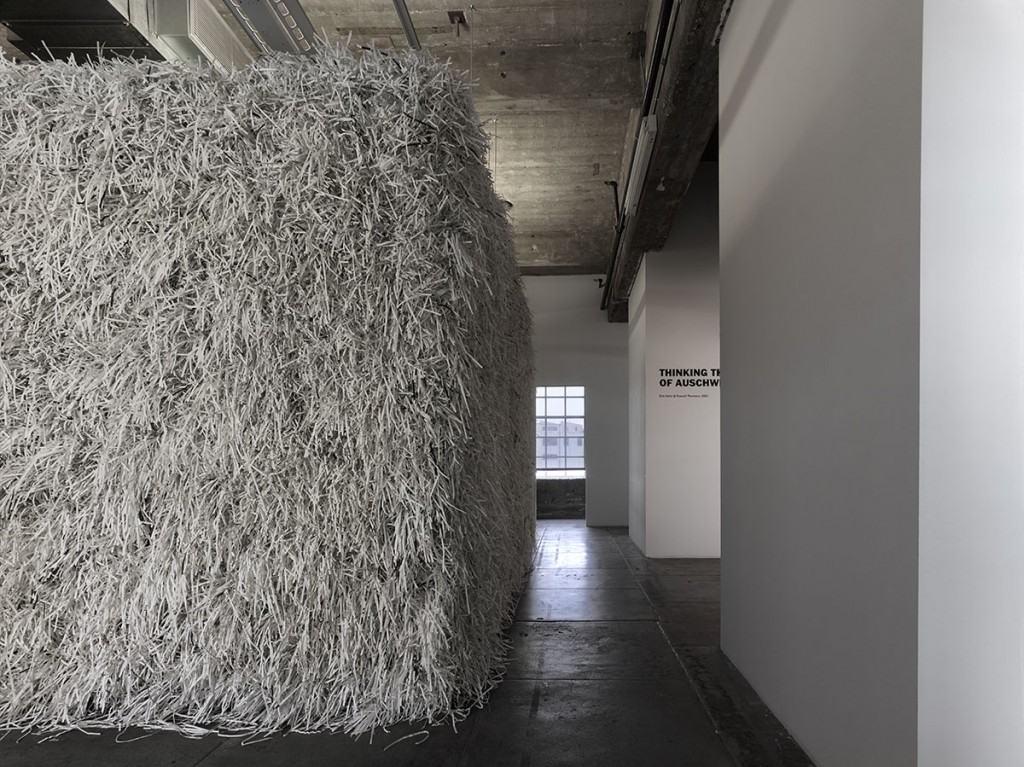

Over sixty years after its liberation, the fragile ruins of the extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau are in steady, rapid decay. Anxious pleas from around the world call for action, either to produce a fabricated restoration, or, as advocated by architectural historian Robert Jan van Pelt, the closure of the physical site after the last victim has passed. Thinking the Future of Auschwitz proposes a third way, one appropriate to the unique significance of the mass, ideological and systematized genocide that occurred there. The two camps—Auschwitz I and Birkenau—are uncoupled, conceptually split. The Auschwitz State Museum maintains its narrative and curatorial role, while Birkenau becomes a Tel Olam. Originating in the Book of Deuteronomy and cited by Dr. Jonathan Webber in his lecture entitled, The Future of Auschwitz, a Tel Olam marks a place where such unspeakable evil occurred it is to be made inaccessible, blotted out perpetually. Our proposal develops a working definition, disciplinary technique and machinic process that provisionally identifies and delimits Birkenau’s traumatic figure. The Tel Olam dismantles, while clearly marking the earth’s surface. It stands as a Mahnmal (warning) in contradistinction to a Denkmal (memorial), and fundamentally alters the mode in which visitors experience the unutterable aspect(s) of Birkenau. Unlike a memorial or museum, which try in earnest to convey meaning in the form of a strong narrative, the Tel Olam provides no such answers. Rather than promoting a sense of common understanding (hastening forgetting), visitors will experience “a place where architecture becomes hermeneutic, probing, questioning, withholding solace and thus closure.”[1] While the project is unique to Auschwitz, it nevertheless contributes significantly to the larger discourse concerning the conventions of catastrophes, suggested by Maurice Blanchot’s text on Auschwitz, Writing Disaster. The Tel Olam conceptually moves Birkenau from the regime of culture towards the regime of nature; eventually the question of its future will emerge again, to be pondered by successive generations. [1] Esther Da Costa Meyer, That Jewish Thing. Artforum, (January, 2006). Project Credits: Dedicated to Eric A. Kahn Links: |